## The City Where Logic Checked Out: Revisiting the Soviet Enigma of Zerograd (1988)

There are journeys in cinema that leave you exhilarated, others that leave you heartbroken. And then there are films like Karen Shakhnazarov's 1988 Zerograd (Город Зеро), a descent into such profound, unnerving absurdity that it feels less like watching a movie and more like waking up in someone else's unsettling dream. It’s the kind of film that, once discovered perhaps on a grainy, nth-generation VHS tape tucked away in the 'World Cinema' section of a long-gone rental store, burrows into your mind and refuses to leave. It doesn't just tell a story; it warps reality until you question the very ground beneath your feet.

### A Simple Trip Gone Sideways

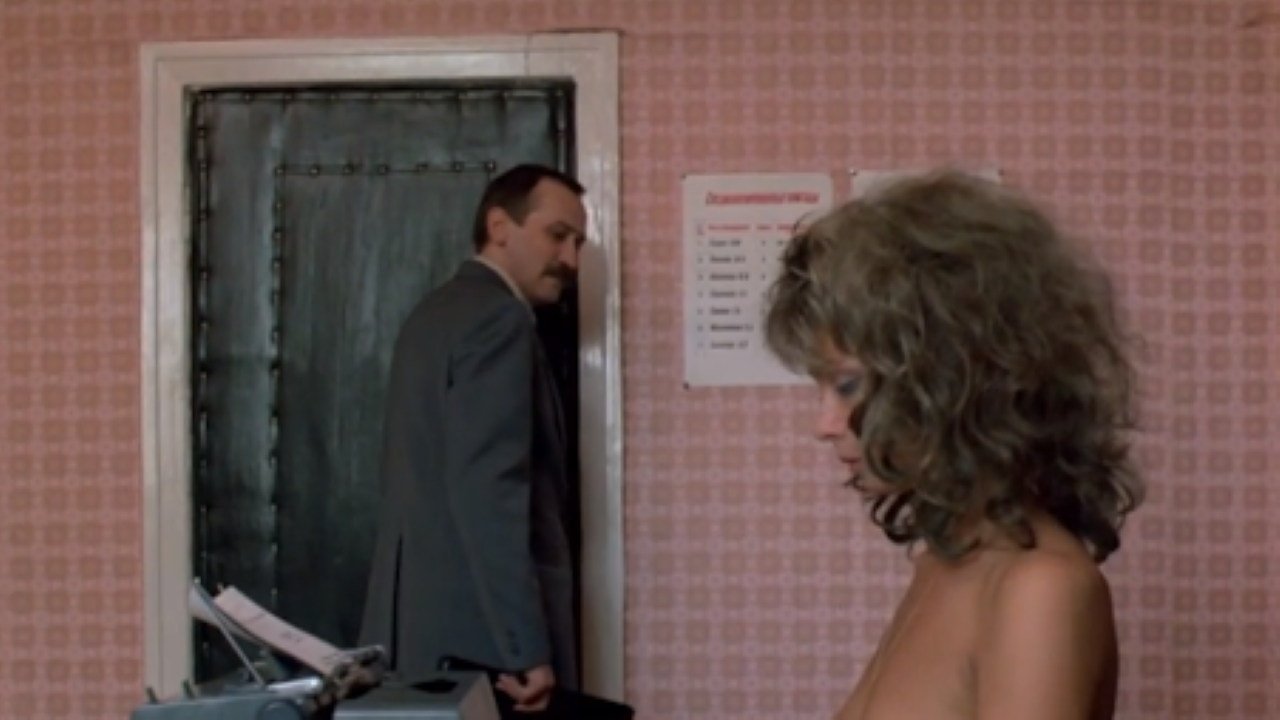

The premise seems straightforward enough: Varakin (Leonid Filatov), an engineer from Moscow, arrives in a nameless provincial Soviet town on a routine business trip. He needs a simple signature from the chief engineer of a local factory. But from the moment he steps into the factory office and encounters a completely naked secretary calmly typing away, surrounded by utterly indifferent colleagues, the mundane shatters. This isn't just an odd occurrence; it's the first crack in a dam holding back a flood of pure, unadulterated strangeness. Finding something like Zerograd nestled between familiar action flicks on the rental shelf back in the day felt like unearthing a coded message from another dimension, a feeling the film itself masterfully cultivates.

What follows is a cascade of increasingly bizarre events. Varakin finds the chief engineer dead, seemingly having waited specifically for his arrival. He's then ushered into a local history museum that defies all logic, presenting exhibits that rewrite historical figures and events into grotesque local myths – including the bizarre assertion that rock and roll originated there. The town, it seems, operates on its own bewildering internal logic, a place where history is mutable, identity is fluid, and escape becomes increasingly impossible. Leonid Filatov is utterly compelling as Varakin, our anchor of bewildered sanity. His performance isn't showy; it's a masterful portrayal of mounting disorientation, a gradual erosion of certainty mirrored in his increasingly haunted eyes. He perfectly captures the feeling of a rational man desperately trying to apply logic to a world that has completely abandoned it.

### Unpacking the Absurdity

Released during the height of Perestroika and Glasnost, Zerograd arrived at a pivotal moment in Soviet history. This context is essential. Was the film a daring satire of the crumbling Soviet system, its bureaucratic inertia, its nonsensical rules, and its tendency to rewrite history? Absolutely, that reading resonates powerfully. The town’s suffocating atmosphere, the characters trapped in inexplicable rituals, the sense of a past being arbitrarily constructed – it all speaks to the anxieties of a society undergoing seismic shifts, where the old certainties were dissolving into something unknown and potentially terrifying. Director Karen Shakhnazarov, working with co-writer Aleksandr Borodyansky, uses surrealism not just for shock value, but as a potent tool for social commentary. It feels less like direct criticism and more like capturing the feeling of living within a system that often felt arbitrary and illogical.

But Zerograd transcends simple political allegory. It taps into deeper, more universal anxieties. What happens when the narratives we rely on to understand the world collapse? What remains when history is proven false, or at least infinitely malleable? The film feels remarkably Kafkaesque, trapping its protagonist in a bureaucratic and existential nightmare from which there is no clear exit. Think of the dinner scene where Varakin is feted by the town's elite, including the local prosecutor played with unsettling gravity by Vladimir Menshov (who himself directed the Oscar-winning Moscow Does Not Cry (1980)). The conversation spirals into madness, culminating in the revelation of a dark town secret and the chilling implication that Varakin can never leave. It’s played with a veneer of normalcy that makes the underlying horror even more potent.

### Echoes in the Static

Watching Zerograd today, perhaps on a cleaner digital transfer than those beloved old tapes, its power hasn't diminished. If anything, its exploration of manipulated narratives and the fragility of truth feels startlingly contemporary. The film’s unique atmosphere – achieved through deliberate pacing, stark visuals, and Eduard Artemyev’s subtly unnerving score – creates a persistent sense of unease. It’s a challenging film, certainly not a comfortable watch, but its refusal to offer easy answers is precisely what makes it so compelling. It doesn't preach; it presents a distorted mirror and invites you to find your own reflection within its strange contours.

One fascinating production tidbit is how the film garnered international attention despite its specific Soviet context, even winning the Gold Hugo at the Chicago International Film Festival in 1989. It struck a chord beyond its immediate political commentary, tapping into that universal fear of losing control, of being swallowed by forces beyond our comprehension. It’s a testament to Shakhnazarov’s vision and the strength of Filatov’s central performance that the film remains so gripping. It’s the kind of cult classic VHS find that truly felt like discovering hidden treasure – weird, challenging, and utterly unforgettable.

Rating: 9/10

Zerograd earns this high rating for its audacious originality, its masterful blend of biting satire and existential dread, and its unforgettable, dreamlike atmosphere. Leonid Filatov's performance is pitch-perfect, anchoring the pervasive absurdity in relatable human confusion. While its deliberate pace and embrace of the bizarre might not appeal to all viewers, its artistic ambition and enduring thematic resonance make it a standout piece of late-Soviet cinema. It's a film that proves that sometimes, the most profound statements about reality are made by shattering it completely.

Decades later, the absurdity of Zerograd feels less like pure fantasy and more like a distorted reflection of the uncertainties we still navigate. What truly lies beneath the surface of the ordinary when the signposts are removed?