There’s a particular kind of damp chill that settles in the forgotten corners of a city, a scent of decay and stagnant water mingling with the metallic tang of old machinery. It’s the smell of the New York subway tunnels in Guillermo del Toro’s Mimic (1997), and it clings to you long after the tape has stopped whirring. This isn't just a creature feature; it's a descent into a bio-engineered nightmare, where humanity's attempt to cure one plague accidentally birthed another, far more insidious threat lurking just beneath the streets.

### The Clicking in the Dark

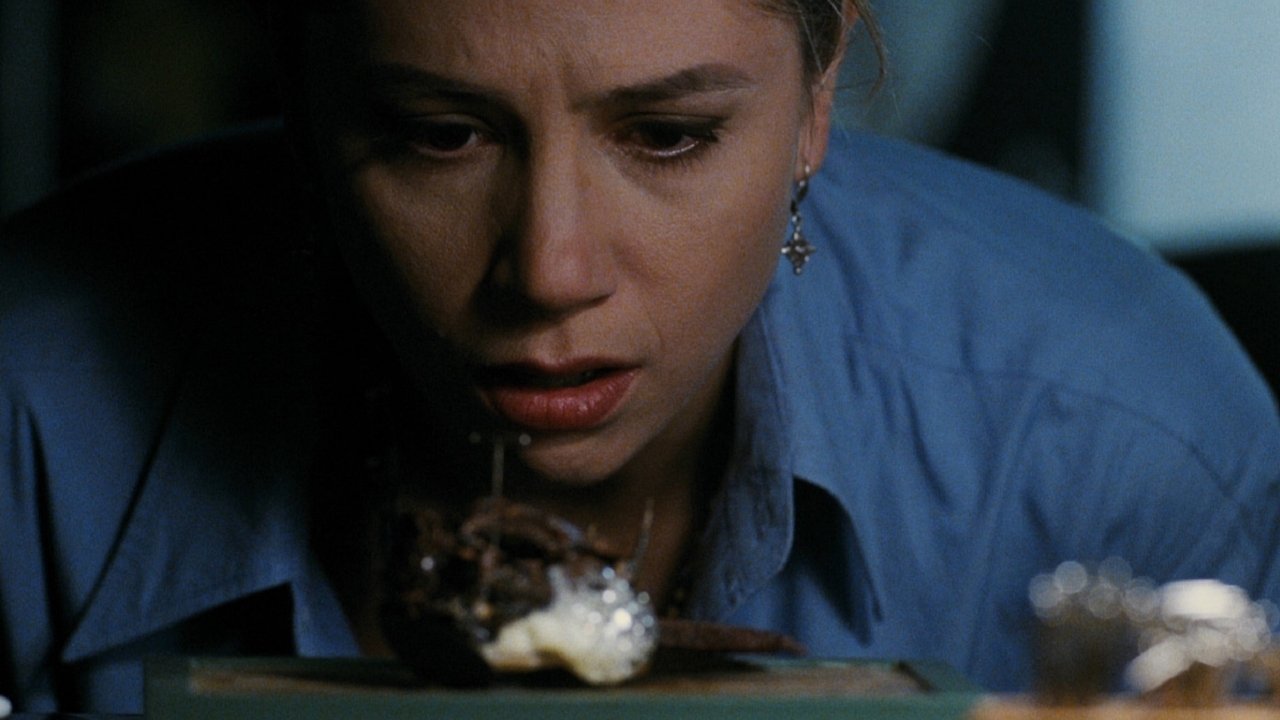

The premise itself taps into a primal unease. Dr. Susan Tyler (Mira Sorvino, bringing a compelling mix of scientific brilliance and maternal instinct, a far cry from her Oscar-winning turn in Mighty Aphrodite just two years prior) engineers the "Judas Breed," a hybrid insect designed to eradicate disease-carrying cockroaches plaguing Manhattan's children. The plan works... too well. Designed with a limited lifespan, the Judas Breed survives, evolves, and begins to mimic its ultimate predator: us. That central concept – giant insects folding their wings to resemble a human figure cloaked in shadow – is pure, distilled nightmare fuel. Doesn't that silhouette still send a shiver down your spine? The genius lies not just in the visual, but in the sound – the wet clicking, the chitinous rustle just out of earshot, suggesting something monstrous masquerading in human form.

### Urban Decay as Character

Del Toro, even in this early, famously troubled production, demonstrates his mastery of atmosphere. The New York of Mimic isn't the glittering metropolis of postcards; it's a labyrinth of crumbling brickwork, leaky pipes, and subterranean darkness. The production design feels lived-in, grimy, and genuinely threatening. You can almost smell the mildew and feel the oppressive humidity of the abandoned subway stations where much of the action unfolds. These aren't just sets; they're extensions of the film's themes – nature reclaiming abandoned spaces, the rot beneath the surface of civilization. The claustrophobia is palpable, trapping the characters (and the viewer) with the horrors below. This film reportedly had a budget of around $30 million, and you can see much of it invested in creating this tactile, decaying world.

### Creatures Born of Conflict

The Judas Breed themselves remain impressive examples of practical and early digital effects blending. Designed by the legendary Rob Bottin (whose genius gave us the horrors of John Carpenter's The Thing (1982)), the insects are genuinely grotesque, slick with ichor, their movements both alien and horribly familiar. Their ability to mimic human form is the film's terrifying trump card, executed with unsettling effectiveness. However, the journey to bring these creatures, and the film itself, to the screen was fraught. Del Toro famously clashed with producers Bob and Harvey Weinstein (Miramax), who demanded more conventional jump scares and a less complex narrative. It's a well-documented struggle, a "dark legend" of studio interference that reportedly left del Toro deeply unhappy with the theatrical cut. He felt his vision, particularly the religious and evolutionary subtext, was compromised. Watching it now, you can sometimes feel the seams where different intentions pull at the narrative. Despite this, the core design and the unsettling concept shine through, a testament to the strength of the original idea sourced from Donald A. Wollheim's short story.

### Faces in the Gloom

Alongside Sorvino, the cast navigates the terror effectively. Jeremy Northam plays Dr. Peter Mann, Susan's husband and colleague, grounding the scientific jargon with relatable concern. A pre-stardom Josh Brolin adds a dose of cynical grit as CDC employee Josh Maslow, navigating the bureaucratic and literal tunnels with weary determination. Character actor extraordinaire Charles S. Dutton steals scenes as Leonard, a skeptical but resourceful transit cop who knows the tunnels like the back of his hand, providing both gravitas and moments of welcome, earthy humor amidst the escalating dread. Their performances help sell the escalating nightmare, reacting to the unseen and the all-too-visible horrors with believable fear. I distinctly remember renting this on VHS, drawn in by the creepy cover art, and being genuinely unnerved by the escalating tension and the commitment of the actors to the sheer horror of their situation.

### Legacy of a Compromised Vision

Despite its troubled production and subsequent underperformance at the box office (grossing around $25.5 million domestically against its $30 million budget), Mimic has endured as a cult favorite within the 90s sci-fi horror canon. Its influence can be seen in later creature features that blend scientific hubris with visceral horror. The later release of Guillermo del Toro's Director's Cut in 2011 allowed fans a glimpse closer to his original intent, restoring some character beats and thematic depth, confirming the long-held belief that a stronger film was hampered by studio demands. This "Mimic 1997 review" wouldn't be complete without acknowledging that context; the theatrical cut available on VHS back in the day felt potent but sometimes abrupt, hinting at deeper layers obscured by the edit.

Rating: 7/10

Mimic earns its score through sheer atmospheric dread, del Toro's undeniable visual flair even under duress, and a genuinely terrifying central monster concept realized with impressive practical effects. The performances are solid, anchoring the fantastical elements in human fear. Points are deducted for the narrative unevenness and occasionally rushed pacing, likely scars from the infamous production battles.

Ultimately, Mimic remains a fascinating, flawed gem from the late VHS era. It’s a potent reminder of Guillermo del Toro’s burgeoning talent and a chilling exploration of urban horror, leaving you glancing twice at shadowy figures huddled in doorways long after the credits roll. It's a film that crawls under your skin, much like its terrifying antagonists.